How to containerize a GitHub Actions self-hosted runner

Launch any number of Github Actions runners on a single VPS or EC2 Instance

The why

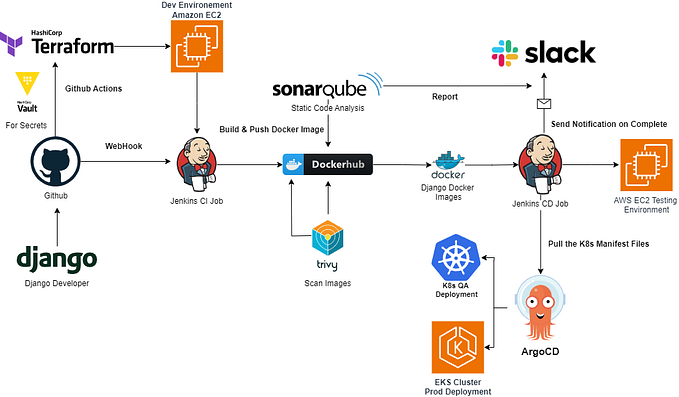

Have you tried using GitHub Actions? Pretty cool right? They allow you to write entirely reusable workflows, so that you can carefully and elegantly design a pipeline for your development environment and then quickly adapt it to your staging and production environments too!

However, unless you’re using them for a small personal project, some issues start surfacing almost right away. The shared runners have laughable amounts of memory and build times start growing and growing, until you loose your patience, scream “That’s it!” and go looking for a solution.

Of course a solution would be to get a pro subscription to GitHub but that’s not really an option is it? Not for me at least. I’m a DevOps guy and I’m gonna do things myself. I will bleed if necessary but I’m not taking the easy way out.

The next best thing is to set up your own self-hosted runner. I honestly was surprised at how easy it was to do. I just spun up a VPS and followed the instructions provided by GitHub and in less than 10 minutes I had my runner. I thought it was pretty amazing. But then I realised that I had driven myself into a corner.

My runner was highly performing but it could only take one job at the time, which is sub-optimal to say the least. If you are building several frontends, Docker images, running tests, etc, several slow runners will probably provide a better performance than a single fast one.

And that’s where the idea came from: “Let’s just run a bunch of these in their own Docker containers on my high-performance VPS!”. And so I got to work.

Disclaimer

This is going to be a basic implementation. In order to launch the runners you will need to have SSH access to your server instance.

In this post I’m going to use a Ubuntu 20.04 instance provided by Vultr.

The plan

- Create a Dockerfile corresponding to the image of a single runner

- Push the image on the Docker Hub

- Access the server

- Install Docker

- Create a compose.yml file

- Launch as many runners as you want

- Clean up

Create the Dockerfile

For the Dockerfile and the start.sh script I was “heavily inspired” by this amazing tutorial on testdriven.io. However I’m going to expand on that tutorial and explain it a little more in depth.

The Dockerfile

ARG DEBIAN_FRONTEND=noninteractiveARG DEBIAN_FRONTEND=noninteractive is necessary or when executing installdependencies.sh the container creation will stop. As you can see from the path /home/docker/actions-runner/bin/installdependencies.sh this is a script that is downloaded with the runner configuration files. No need to look too much into it.

RUN apt update -y && apt upgrade -y && useradd -m dockerRUN apt install -y --no-install-recommends \curl jq build-essential libssl-dev libffi-dev python3 python3-venv python3-dev python3-pip

So first thing we update and upgrade Ubuntu package library and we install some required packages. Most notably curl and jq. Then we add a user called docker which we will use to perform all the operations. This is important because GitHub Actions runners can’t be launched by the root user.

RUN cd /home/docker && mkdir actions-runner && cd actions-runner \&& curl -O -L https://github.com/actions/runner/releases/download/v${RUNNER_VERSION}/actions-runner-linux-x64-${RUNNER_VERSION}.tar.gz \&& tar xzf ./actions-runner-linux-x64-${RUNNER_VERSION}.tar.gz

Now we run the GitHub Actions commands. We create a a folder called actions-runner in the user’s home folder and we cd into it. From there we curl the action runner download link and we extract the files.

RUN chown -R docker ~docker && /home/docker/actions-runner/bin/installdependencies.shYou probably know the chown command but I’m going to explain this particular instance of it anyway.

chown stands for change owner. So with this we are changing the user who owns a file or a set of files.

docker is the name of the user we created earlier.

~docker refers to a path. ~ in bash means ‘home’. And ~docker indicates the home path of the docker user.

-R means that the operation is to be performed recursively. This is common when executing operations on the filesystem because you might not be aware of how many levels deep is the tree inside a certain directory. This means essentially keep going until you’ve hit every subdirectory and every file.

So to sum up, this instruction means: take all files and directories in the home directory of the docker user and make thedocker user the owner of all of them.

COPY start.sh start.shThis instructs docker to grab a sibling file called start.sh and to copy it in the image under the same name.

RUN chmod +x start.shThis opens the execution permissions for the start.sh file in the image, to make sure that it can be executed without issues.

USER dockerSince the config and run script for actions are not allowed to be run by root, set the user to docker so all subsequent commands are run as the docker user.

ENTRYPOINT ["./start.sh"]The image ENTRYPOINT is the first command being executed when the Docker image is run. It can be combined with CMD for more advanced behaviors.

The image start script

Important notice: this script relies on the parameters

REPOandTOKENbeing passed to it. We will see how to do that at a later stage.

We have created an image that contains everything that we need to execute a runner: the various dependencies, the runner source files, a docker user, but in order to activate the runner and have it connect to our GitHub repo we need to perform some more advanced operations, which would be annoying if not impossible to define from the Dockerfile.

What we are setting out to do here is to make an API call to GitHub and get in response a Registration Token. A registration token is an identifier that allows us to register a runner. The tokens are created at the moment and then our repo’s GitHub Actions will only accept runners that attempt to register using a token that was created by it.

Then we will use that token to execute the config.sh script contained in the runner files. This will contact the GitHub Actions server and automatically connect.

REG_TOKEN=$(curl -X POST -H "Authorization: token ${ACCESS_TOKEN}" -H "Accept: application/vnd.github+json" https://api.github.com/repos/${REPO}/actions/runners/registration-token | jq .token --raw-output)The response from the curl is assigned to the variable REG_TOKEN .

cd /home/docker/actions-runnercd into the actions-runner directory in the docker user’s home dir

./config.sh --url https://github.com/${REPO} --token ${REG_TOKEN}Running the config.sh script with url and token parameters

cleanup() {echo "Removing runner..." ./config.sh remove --unattended --token ${REG_TOKEN}}trap 'cleanup; exit 130' INTtrap 'cleanup; exit 143' TERM

We define a cleanup() function which executes the config.sh script with the remove command and the unattended flag (and token parameter). Then below we define two signals: if the shell receives the SIGINT or SIGTERM signals, it will execute the cleanup() function and exit with codes (respectively) 130 and 143 .

If you want to know more about the trap command follow this link. And this completes part! Next we will build the Docker image and push it to our registry.

Build and push the runner image to Docker Hub

Note: You can use whatever container registry you want. Here I’m using the public Docker Hub registry because it’s easy to use and doesn’t require additional steps later to login. In order to follow along with this tutorial you must have an account at hub.docker.com

You can find thousands of tutorials on this particular bit, but I added it anyway for completeness.

From the folder where you are storing your Dockerfile and start.sh script run the following commands:

docker build --tag <your-docker-hub-username>/actions-image:latest .This builds the image and prepares it to be shipped.

docker push <your-docker-hub-username>/actions-image:latestThis pushes it on the Docker Hub as a public image.

Great! Next we’re gonna SSH into our server and write the compose.yml file!

Setting up Docker

I have written a simple script to install and setup Docker on an Ubuntu 20.04 machine. You can check it out here.

Simply create a new file in your server instance and copy the contents from dockerconf.sh and then execute it with source dockerconf.sh

You can do that wherever you like in the server, just maybe avoid system folders. The script must be run with sudo privileges.

Preparing the compose.yml file

Once Docker is up and running on your server, all that’s left is to download and execute the GitHub Actions image you created earlier. You can run said image as many times as you want, and each time it will spawn an independent runner.

There are two ways to go about it. The first one is to run the image directly with docker run but I dislike this method because it requires you to manually enter your GitHub Token and your repo name every time.

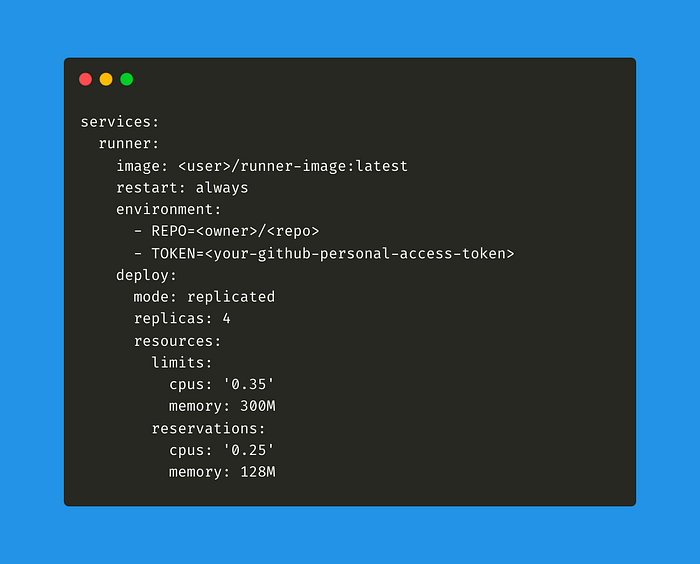

My preferred method is to create a compose.yml file and store these parameters in there as environment variables.

Now, before launching 8000 runners on your server you should take into account memory usage. From the Docker docs:

It is important not to allow a running container to consume too much of the host machine’s memory. On Linux hosts, if the kernel detects that there is not enough memory to perform important system functions, it throws an

OOME, orOut Of Memory Exception, and starts killing processes to free up memory. Any process is subject to killing, including Docker and other important applications. This can effectively bring the entire system down if the wrong process is killed.

So it’s important to include in your compose.yml file some instructions to make sure that your server doesn’t blow up. Unfortunately these instructions have to be hardcoded and have to be tailored on the actual memory at your disposal.

An instance of Ubuntu server needs a minimum of 512Mb of memory and one 1Gh CPU. At my disposal I have a 2 vCPUs server with 2048Mb of RAM, so I opted to give each of my runners a share of CPU ranging from 25% to 35% and memory ranging from 128Mb to 300Mb. You should configure these limits based on the resources available on your machine.

Notice how I’ve added mode: replicated and replicas: 4 . It’s a shortcut to make sure that the same image is used to spawn four containers. Alternatively you can run docker compose with the --scale flag and then indicating which container to scale (example below).

docker compose up --scale runner=4And with this, Docker will spawn 4 different containers from the same image. Each one of them will have a different registration identifier and will pose as an individual, independent self-hosted runner.

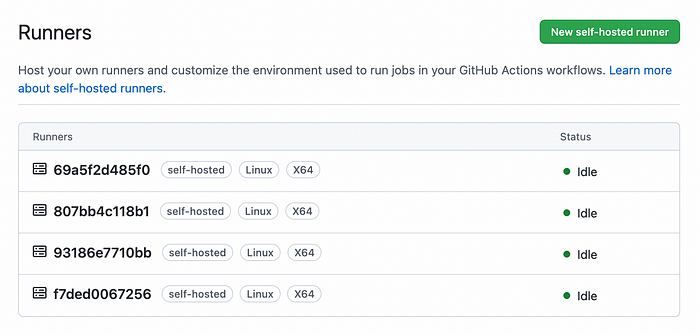

Result

Cleaning Up

The second half of the start.sh script aims at cleaning up after itself when the docker container that hosts the runner is stopped. However it comes with a limitation: it’s able to intercept the SIGINT and SIGTERM signals but not a SIGKILL signal. The reason is simple, SIGINT and SIGTERM kind of politely request that the process is terminated, SIGKILL shoots the process in the face, so there’s no time to execute any fancy code.

If you Ctrl+C your docker process, it will send a SIGINT signal. If you mash Ctrl+C multiple times because you are impatient and you need those extra 30 seconds for something else, docker will receive a SIGKILL signal and just stop what it’s doing.

This won’t give it enough time to make the API call to GitHub and dismiss the runners. Those runners will just appear offline from the GitHub Actions UI but in truth they will be dead, worse than dead actually, they will be zombies. So how to remove them?

With this script.

source delete-runners.sh <user/repo> <github_token>Writing this script took some effort, and it forced me to somewhat learn how jq works. If you wish to know more about it let me know in the comments and I will expand this section.